Pencil

In the 1840s, the American slate pencil factory situated in West Castleton, Vermont was the primary producer of slate pencils in the United States. The light-colored, soft material known as soap-stone slate, quarried from the Slate Valley, was considered to be of the finest quality. Beginning around 20 years prior to the American production of slate in Vermont, however, Germany supplied a hard, dark, grit-filled version of the slate pencil (Maine Journal of Education 1871, 24).

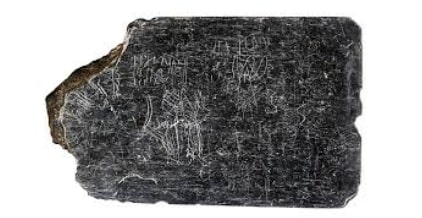

The slate pencil found in the buried remains of the Wilson house in Seneca Village (Figure 1) most closely resembles the German model, suggesting it had been manufactured in Germany and imported to the States.

Paired with a slate tablet, the slate pencil was a common utensil that had long been used for many purposes, such as record-keeping during trade, tracking family expenses, or learning to write. Figure 2, for example, shows a slate tablet with a variety of markings excavated in Jamestown, VA, at the site of the first permanent English settlement in what would become the United States (Historic Jamestowne, n.d.). With a family of eight children, it is most likely that the Wilsons’ slate pencil was most frequently used for educational purposes.

Figure 1: Image of dark, 4.5 cm slate pencil from Wilson House. (Photo Courtesy of NYC Archaeological Repository)

Family Hopes

In the 1855 New York State Census, William Godrey Wilson was recorded as the head of his household, which consisted of himself, his wife “Charlot[te]” Wilson, and their eight children. This census indicates that William Wilson worked as a porter, while records from the Episcopal All Angels’ Church that had been located next to the Wilson’s home, indicate that he was also the sexton (caretaker) of the church. An iron curry comb found at the site suggests that one of his jobs may have involved grooming horses. Charlotte Wilson, the mother, likely cooked, cleaned, and completed household chores–women typically performed domestic labor during this time period (Blackmar 2019, 53). All of the Wilson children attended school, which was a priority until they were old enough to get a job (USBC 1850, NYSC 1855). The eldest son was the first to enter the workforce at the age of 17 (perhaps after completing secondary school) as a waiter (NYSC 1855). The younger children were not employed while in school and most likely participated in household chores. The Wilsons may have wanted their children to focus on receiving a strong educational foundation before they considered, or were required, to work.

Sending children to school was a common aspiration among the larger Black community in New York during the nineteenth-century, such as residents in Five Points and other downtown neighborhoods, who believed that education would permit success and equality among Black and white groups in New York because it could shape character, morals, values, and intellect among successive generations (Peterson 2011, 65).

It is thus likely that William Godfrey Wilson and Charlotte Wilson believed that educating their children would enable them to obtain better opportunities in society. Unfortunately, discrimination would be a constant pressure upon Black lives, inhibiting their ability to fulfill such expectations. After they were forced to leave the village, the Wilsons moved with All Angels’ Church a few blocks to the west and their sons took on the service jobs such as a butcher, coachman, and a waiter (USBC 1870), thus proving their limited work opportunities despite their education.

Also important is that the parents sent their daughters to school as well as their sons. It had been a long-established norm among both Black and white families to educate boys before (or instead of) girls (Wall, Rothschild, Copeland 2015, 103). In fact, Charlotte Wilson, like many other women, was recorded as illiterate on the 1850 Federal Census, while her husband was recorded as literate. Black girls and women, in particular, were often forced into domestic work or wage-earning jobs instead of school in order to provide for their families. This was because the wages earned by their husbands or fathers from labor intensive, low paying jobs, were insufficient to support an entire family (Dabel 2008, 41-42). Charlotte Wilson may have hoped that an education would allow her daughters to become socially engaged members of society and to achieve more opportunities as Black women, instead of being limited to domestic work. Of course, there would be a long way to go before women could freely participate in society.

Figure 2: Slate tablet with inscriptions made by slate pencil from Jamestown, VA. Source: Historic Jamestown

Education at Home

For the Wilson family, fostering education probably did not take place solely in school. The slate pencil associated with the Wilson house comes from an assemblage of other household items: scissors, a spoon, thimble, pan, kettle, hinge, and utensil handle, for example. All of these items seem unrelated but are much like the random objects we have lying around our homes that are readily available for us to use. Thus, as frequently as a thimble may have been used to sew a hook and eye onto a dress, or a kettle used to heat water, or a spoon used to eat, the slate pencil was actively being used at home, likely to practice writing and math.

We can imagine education was communal because the slate pencil was available at home, where all the children reconvened after school, likely sharing knowledge with each other and assisting one another with schoolwork. Perhaps the children utilized the Lancasterian method of schooling, observed in Downtown schools, where teachers instruct older students, who, in turn, teach younger students. With all her children attending school, Charlotte Wilson may have been exposed to a fair amount of reading, writing, and math allowing her to pick up literacy and math skills bit by bit. In fact, we see her literacy status changed in the censuses from illiterate in 1850 to being able to read in 1855 to being able to both read and write in 1860 (USBC 1850; NYSC 1855; USBC 1860). Educating her children appears to have been a way for Charlotte to return to something she had not been able to attain in her own youth.

Education Outside of the Home

Seneca Village seemed to have had different schooling from the rest of the city. Downtown, African American children could attend the African Free School. The school was established by the New York Manumission Society (an organization founded by prominent white leaders, including John Jay and Alexander Hamilton) in 1785 to promote the abolition of slavery and the protection of freed and enslaved New Yorkers (Figure 3). The African Free School strived to provide an education for Black children in the 1830s under the New York City Public School system (McCarthy 2014). In the 1840s, the Black-managed Society for Education among Colored Children was successful in creating several schools that offered secondary education for Black children, and it was later taken over by the Board of Education (Hodges 1999, 243). Due to the strong racial discrimination at the time, integrating Black and white children in schools was a difficult task.

Compared with these surrounding circumstances, Seneca Village differed greatly. As opposed to having multiple schools and tiered education, Colored School #3, located in the basement of the African Union Methodist Church, was the only primary school operating in the village in the 1840s (Wall, Rothschild, Copeland 2015, 101). With the Episopal All Angels’ church joining the community as the first to have integrated congregations in the late 1840s, it is possible that Colored School #3, too, held spaces for both white and African American pupils to learn.

Education was more accessible to Seneca Villagers than it was for other Black communities downtown in New York, like Little Africa. Despite there being a primary and secondary school for children to attend in Little Africa, only about half of the population attended school while in Seneca Village, three quarters attended school. Families in Little Africa were probably not able to provide resources for their children to attend school or relied on their children to work in order to provide for the family, and may have often kept children at home in fear of their safety amidst riots circulating in 1834 (Wall, Rothschild, Copeland 2015, 103).

The greater percentage of schoolchildren in Seneca Village suggests that parents were more financially stable. Perhaps they preserved their money through self-sufficient practices, like fishing, cultivating crops, and raising animals, so they could afford to send their children to school. In fact, they encouraged children to further their education, as more than half of the older children attended upper school either by traveling downtown or commuting to a non-public school close to home, since there was no upper school in Seneca Village (Wall, Rothschild, Copeland 2015, 103).

As for who taught at the schools, it is speculated that the teacher at Colored School #3 was Catherine A. Thompson, who earned an annual salary of $200 (Croswell 2007, 864). According to the 1855 NY State Census, both Catherine A. Geary (25 years at the time) and her sister Eleanor Geary (18 years) were Irish American female teachers in the village. Whether or not Catherine A. Thompson and Catherine A. Geary were the same person is a question yet to be answered, but the presence of white female educators in a predominately African American village during the 1850s might speak to the cooperation of people from differing backgrounds in Seneca Village. It is worth noting the female presence in education in Seneca Village prior to the establishment of the Female Normal and High School or the Normal College of New York in 1869 which, for the first time, trained female educators using a strong, wide ranging curriculum. Before then, females were only trained in 9 AM-2 PM Saturday schools with poor instruction and limited subjects (Roff 2018).

Figure 3: Drawing of African Free School Number 2 by student P. Reason. Source: New York Historical Society

Where are Slate Pencils now?

Slate pencils and like tools, such as chalk, are not used as commonly today. Other forms of writing utensils have dominated the stage (Figure 4). They include yellow or orange wood-encased graphite pencils with red rubber erasers and colorful mechanical pencils. While mechanical pencils tend to be priced a little higher, the wood-encased pencils are the most inexpensive and do the job well. Styles of learning have also evolved as writing tools changed. 19th-century students relied on their memory to retain their notes after they wiped their tablets for a new lesson (Marvel 2012). Students would have to be extremely conscious of how they were recording information, ensuring that it was accurate. Today, with the addition of an eraser, we have the privilege of erasing our mistakes, rewriting, and refining our work. Nevertheless, whether it is a slate pencil on a slate tablet or a graphite pencil on paper, the necessity of instilling at least rudimentary literacy skills remains undeniable.

Works Cited

Blackmar, Elizabeth. 2019. “Housework and Homework in 19th-Century New York City.” In City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York, edited by Joshua B. Freeman. New York: Columbia University Press, 52-63.

Dabel, Jane E. 2008. A Respectable Woman: The Public Roles of African American Women in 19th-Century New York. New York, NY: NYU Press.

“Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Issue 50.” 2007. Google Books. New York: E. Croswell.

Duane, Anna Mae, and Thomas Thurston. n.d. “The History of the School.” Examination Days: The New York African Free School Collection. Russell Sage Foundation. https://www.nyhistory.org/web/africanfreeschool/history/history.html.

Historic Jamestowne. n.d. “Slate.” https://historicjamestowne.org/collections/artifacts/slate/.

Hodges, Graham Russell. 1999. Root & Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613-1863. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Maine Journal of Education. 1871.“SLATE PENCILS—HOW AND WHERE THEY ARE MADE.” 5(1): 24-29. www.jstor.org/stable/44859825.

Marvel, Mrs. 31 Aug., 2012. “Slates & Slate Pencils.” Mrs Brewer’s Parlour. Past Periods Press (blog). https://pastperiodspress.com/2012/08/31/slates-slate-pencils/.

McCarthy, Andy. 2014. “Class Act: Researching New York City Schools with Local History Collections.” New York Public Library. Milstein Division of U.S. History, Local History & Genealogy. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2014/10/20/researching-nyc-schools.

New York City Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center. 2020. “Seneca Village.” NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York, NY. http://archaeology.cityofnewyork.us/collection/map/seneca-village.

New York State Census (NYSC). 1855. Census Returns for the Sixth Ward of the City of New York in the County of New York. Manuscript, Department of Records and Information, Municipal Archives of the City of New York, New York, NY.

Peterson, Carla L. 2011. Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Roff, Sandra. 2018. “The Struggle for Teacher Education in 19th Century New York.” The Gotham Center for New York City History. https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/the-struggle-for-teacher-education-in-19th-century-new-york.

United States Bureau of the Census (USBC). 1850. Population Schedules of the Seventh Census of the United States, 1850. Research Division, New York Public Library, New York, NY.

United States Bureau of the Census (USBC). 1860. Population Schedules of the Eighth Census of the United States, 1860. Research Division, New York Public Library, New York, NY.

United States Bureau of the Census (USBC). 1870. Population Schedules of the Ninth Census of the United States, 1870. Research Division, New York Public Library, New York, NY.

Wall, Diana DiZerega, Nan A. Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland. 2008. “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City.” Historical Archaeology 42(1): 97-107.