Eye (from hook and eye)

Figure 1 shows a copper alloy hook and eye excavated from the Wilson house in Seneca Village.

Background

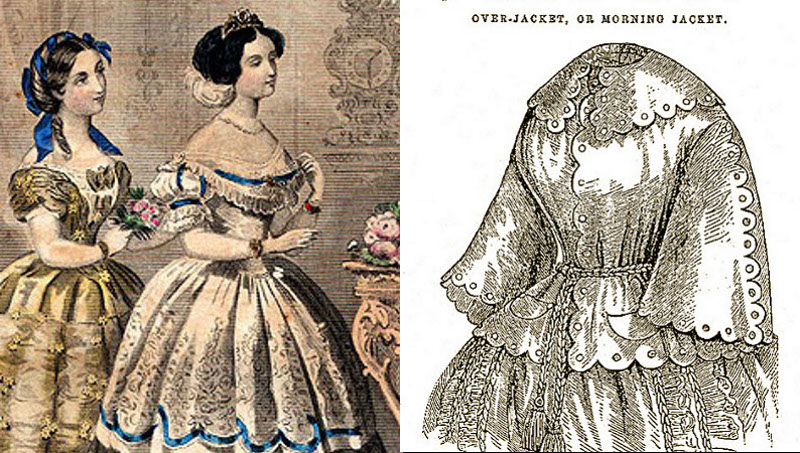

Hooks and eyes were a common way of fastening clothing in the nineteenth century. Many types of artisans produced and sold them directly to consumers (White 2005, 75). They were sewed as closures onto women’s bodices, Berthas (“a decorative piece added to a low-necked bodice,” shown in Figure 2), men’s overcoats, jewelry, etc. (Fleming 2014). Because hooks and eyes were a more versatile, simple, and cheap fastener option than buttons, clasps, and buckles, they were used by folks of all socioeconomic classes (White 2005, 75). Today, one of their well known uses is bra clasps.

Figure 2: Although it is unclear from the picture, this Bertha’s back closure may have been a hook and eye. Regardless, it is an example of the type of clothes a hook and eye could be fastened to.

Gender Context

Even though men produced and manufactured hooks and eyes, women were the ones who sewed them onto clothing. Originally, this kind of work was not gendered, but by the nineteenth century, sewing and femininity were fused, meaning women were expected to do the sewing. This kind of work was and still remains undervalued. However, without women’s (particularly Black women’s) work, civilization could not advance. Without their labor, “the course of civilization, if indeed there was any, would be unimaginable, unthinkable” (Beaudry 2006, 5). A world without women’s sewing is a world without essential inventions and historic moments. One could not thrive if one was not wearing proper clothing. The Confederate Army may have won the Civil War had the Union Army all lacked proper warm attire. Albert Einstein may not have been taken seriously without donning his sweaters. The list goes on.

Work and Agency

Women were not solely sewing in their own homes for their own families. They also sewed in factories, took home piecework, and/or sewed other families’ clothes for profit (pictured in Figure 2; Stott 1990, 102; Wall 2008, 104). These forms of work enabled women to earn money for their families and forge some independence. Going into work and claiming the responsibility that came with it was empowering. Yet, Black women were constantly discriminated against in the workplace, and women overall were considered a less important part of the workforce (Wall 2008, 97). Their insufficient compensation made that clear (Stott 1990, 107). Women who sewed in domestic spaces, either for their own or for someone else’s family, would also be considered insignificant. Even though women’s work was belittled, their work and its minimal salary (if they were working for others) led to more opportunities. Just like the fishing weight, curry comb, and slate pencil linked below, hooks and eyes, and the work that came with them, created a path to some self-sufficiency and subsequent freedom.

Figure 3: Fox, Stanley, 1868. “Women and Their Work in the Metropolis.” Harper’s Bazaar, April 18th, 1868. These beautiful engravings capture moments of women’s working lives.

Hooks and Eyes in New York City

Dry goods merchants, as well as the artisans ( jewelers, clockmakers, and pin makers) who made these fasteners, sold hooks and eyes; the high concentration of merchants and artisans in the metropolis ensured that New Yorkers could purchase hooks and eyes all over the city (White 2005, 75). Historical documents allow us to sometimes identify the particular individuals who sold them. For example, an account book of the jeweler Charles Osbourn shows that he “inventoried two dozen… [and] one gross of hooks and eyes” (one gross is equivalent to one hundred and forty-four) in New York City in 1814 (White 2005, 76). Hooks and eyes’ availability only grew over time.

Seneca Village

In Seneca Village, Charlotte Wilson might have sewed hooks and eyes onto other people’s clothes for profit. She might have sewed them onto her own families’ clothes, or simply mended tears on clothes with hooks and eyes. Perhaps Charlotte did not sew this particular hook and eye at all, and it instead was a part of a piece of clothing that she or one of her family members wore. There was at least one dressmaker who lived in the village in 1855 named Eliza Geary, who may have used hooks and eyes on her dresses (NYSC 1855). Perhaps the Wilsons purchased a dress from Eliza for Charlotte or her daughters, Charlotte and Mary. As a porter who likely worked outside year-round, William Godfrey Wilson may have relied on a hook and eye to keep his coat closed snugly around his chin during the cold winter months (NYSC 1855). Their son, William H. Wilson, may have fastened part of his waiter’s attire with a hook and eye (NYSC 1855). Although the artifacts are small in size, hooks and eyes were significant parts of life in Seneca Village. Not only can they be used by historians to gain a greater understanding of the gender and work dynamics of the time, but they also illuminate more about the everyday experience of living there.

Works Cited

Beaudry, Mary C. 2007. Findings: The Material Culture of Needlework and Sewing. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fleming, R.S. 2014. “Victorian Fashion Terms; A-M.” Last Modified October 28th, 2014. http://www.katetattersall.com/victorian-fashion-terms-a-m/.

Fox, Stanley. 1868. “Women and Their Work in the Metropolis.” Harper’s Bazaar, April 18th, 1868.

Freeman, Joshua B., ed. 2019. City of Workers, City of Struggle: How Labor Movements Changed New York. New York; Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press.

New York State Census (NYSC). 1855. Census Returns for the Sixth Ward of the City of New York in the County of New York. Manuscript, Department of Records and Information, Municipal Archives of the City of New York, New York, NY.

Stott, Richard B. 1990. Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity, and Youth in Antebellum New York City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Wall, Diana diZerega, Nan A. Rothschild, Meredith B. Linn, and Cynthia R. Copeland. 2018. “Seneca Village, A Forgotten Community: Report on the 2011 Excavations.” New York, NY: Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History, Inc. A report submitted to NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, the Central Park Conservancy, and the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation.

Wall, Diana di Zerega, Nan A. Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland. 2008. “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City.” Historical Archaeology 42 (1): 97–107.

White, Carolyn. 2005. American Artifacts of Personal Adornment 1680-1820. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.