Curry comb

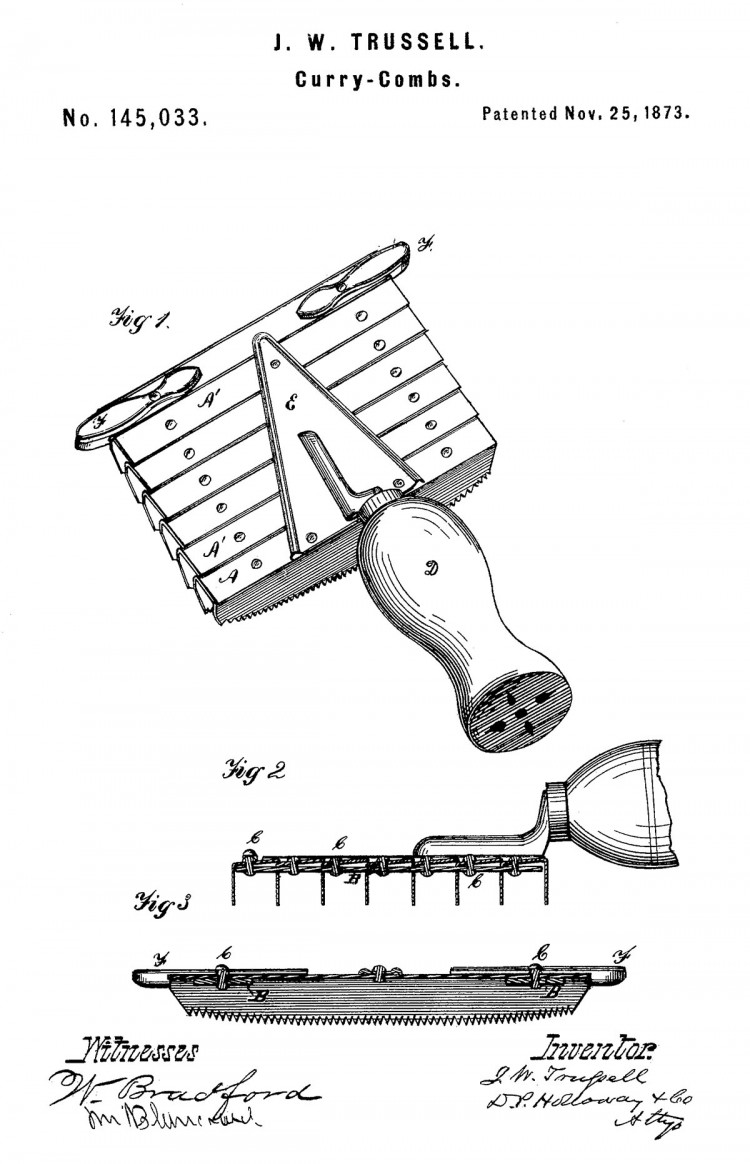

The significance of horses in 19th century New York City could not be overstated, and range from military purposes to urban transportation. Curry combs were used in order to maintain their muscular health and preserve their coat. While we tend to see plastic or silicone versions today, this iron model found in Seneca Village (Figure 1) served the same essential purpose. Though in several pieces, the gist of the comb’s construction can be understood–a handle (now missing its wooden portion) fitted with a base connects to two bars, the teeth of which would rake through the horse’s hair and dislodge any dirt or dried manure.

Figure 1: Iron Curry Comb from Wilson Household. (Photo courtesy of the NYC Archaeological Repository)

Curry Comb Production

The production of curry combs was amplified after the Industrial Revolution popularized metal mass-production; they initially had been handcrafted and artistically designed for the upper class. A more utilitarian design was implemented when items were able to be formed, replicated, and imported in bulk, all while enhancing the local coal industry (Knopp 2011). By the end of the eighteenth century, curry combs and other iron products were routinely exported to America. The comb found in the Seneca Village excavation was likely imported, given that American patents for curry combs were not designed or produced until at least 1856, when Major Peter V. Hagner became frustrated with the quality of English curry combs and was “convinced this item could be made at ‘our Arsenals’ in better quality by using steel plate instead of iron and ‘changing a little the style of manufacture at a small increase in price’” (Knopp 2011). Though it was patented in 1873, Figure 2 shows one such utilitarian design of a curry comb, the pieces of which are recognizable even on the model found in Seneca Village.

Figure 2: Curry Comb Design (1873). (Photo courtesy of the NYC Archaeological Repository)

Horses in New York City

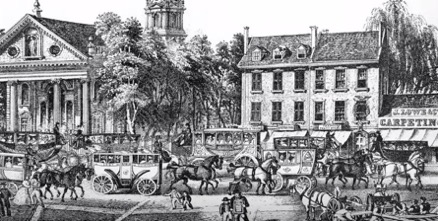

As for horses in New York, the necessity for them was at an all-time high. The city was expanding rapidly as neighborhoods were established and land was claimed. The need to simply move around effectively was becoming crucial, and horse-buses (omnibuses) were the first major form of such public transit. While carriages drawn by horses were nothing new, these omnibuses (Figure 3) originated in 1827 and ran along a designated route (Bellis 2019). Able to carry larger groups of people, they were much more affordable options. Equivalent to our modern commuter buses, omnibuses were marketed as open to any and everyone.

While these omnibuses were certainly less expensive than individual carriages, they were not as open to all citizens as photographs and illustrations lead us to believe. The everyday worker could likely afford a ticket, but the daily expense added up, and it was incredibly risky for an average laborer to spend so much income on transportation alone. Discrimination was another critical factor, as “African Americans could not count on being able to travel by public transportation on the new omnibuses, cross-country stages, or European packets. In fact, they could not use public transportation without discrimination until after the Civil War…” (Wall, Rothschild, and Copeland 2008, 97). Blatant legal discrimination on omnibuses may have ended, but societal discrimination was far from over. Like many of America’s institutions, omnibuses were not nearly as “equal for all” as they claimed.

Figure 3: 1830 Omnibuses Along Broadway. (Memorial History of the City of New York)

Seneca Village Curry Comb

The curry comb’s presence in Seneca Village raises several unanswered questions, but a few key facts can help piece together its narrative. It was found in the ruins of the home owned by William Godfrey Wilson for a few years prior to Central Park’s construction. All Angels’ Church records confirm that he was the sexton of the church, but the 1855 New York State Census states his occupation as a porter, carrying goods from place to place. This is likely the best explanation for the presence of a curry comb in the village, since African American men “tended to work as unskilled laborers, as service workers (barbers, waiters, coachmen, or porters), or as sailors” due to the difficulty of finding work elsewhere; many white citizens openly expressed their refusal to work alongside freed African Americans, regardless of their skill level in those fields (Wall, Rothschild, and Copeland 2008, 97). While many Seneca Village properties had sheds on the perimeter of their land, it is unclear what the explicit purpose of these sheds was. Some are presumed to be outhouses given their position on the property–as far away from the house as possible–but others appear far too large to be outhouses. They may have housed smaller animals (such as sheep or goats), but this too is unclear. As far as we know, there is no confirmation of a shed or a stable, the type of structure most likely used to keep a horse, on the Wilson property. The comb, however, suggests that a horse was utilized in William Godfrey Wilson’s work, even if said horse was stabled elsewhere.

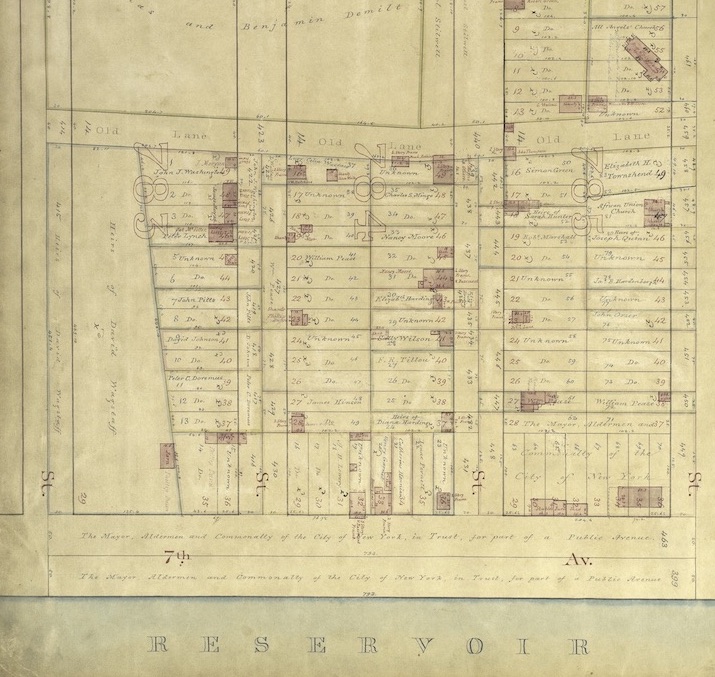

Stables and barns were present in Seneca Village, a few of which were within the general vicinity of the Wilson household. The Central Park Condemnation Map (Sage 1856) outlines in red most of the structures in the village and labels their purpose (if known). There were three structures labeled stables between 83rd and 88th Streets, with a few barns, in addition. (Figure 4 shows a section of the map between 82nd and 85th Streets.) Any of these could have been accessible to William Godfrey Wilson, but whether or not he interacted with the horses housed in these particular stables is not known. The title of porter had a vague definition in the nineteenth century; while today we define their work as carrying luggage, the term was much more lenient in Wilson’s time, and he could have been carrying goods of any sort. Access to (if not ownership of) a horse would certainly be advantageous in such an industry, and using horses in transportation was becoming increasingly more normalized during the time of Seneca Village. Given the rampant discrimination that free African Americans were subject to on omnibuses, private usage of a horse could have alleviated the external stressors of traveling outside of the village and working in other parts of the city.

Figure 4: 1856 Sage Condemnation Map

Connection to the Present

Curry combs have endured several transitions over the course of history, from lavish designs for the wealthy to utilitarian models and their modern silicone counterparts. Their function is far more trivial now (since horses are no longer critical in the military or for most people’s commute) and thus their historical significance has suffered–it is an “article of military material culture that has languished in obscurity and neglect… Overwhelmed by confusing multiple patterns, hampered by little historical documentation, even less understanding and no respect as a collector’s item, the lowly curry comb has sadly been relegated to the junk box of indifference” (Knopp 2011). A curry comb is a horse owner’s accessory. It is likely no less beneficial to their muscular health and general appearance as it once was, but horses themselves are no longer utilized in the general workforce. This transition is arguably favorable when considering the harsh conditions of work-horses, especially before any discussion of animal rights. Their presence in New York City has diminished, other than the occasional horse carriage or mounted police officer–both systems that have been the subject of bitter contention for years. To Seneca Villagers, however, horses may have been a valuable instrument of agency, serving as a form of transportation that was self-contained and self-driven. Much of the work done in Seneca Village reflects those ideals, and such history is nothing if not admirable.

Works Cited

Bellis, Mary. 2019. “Andrew Steele Hallidie and the First Cable Cars.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-streetcars-cable-cars-4075558.

Knopp, Ken R. 2011. “American Curry Combs: History & Identification.” Confederate Saddles & Horse Equipment (blog). http://confederatesaddles.com/2011/05/18/american-curry-combs-history-identification/.

Wall, Diana DiZerega, Nan A. Rothschild, and Cynthia Copeland. 2008. “Seneca Village and Little Africa: Two African American Communities in Antebellum New York City.” Historical Archaeology 42(1): 97-107.