Wine bottle

Seneca Village was a community of free African Americans and European immigrants (mostly Irish) that existed in Uptown New York City between 1825 and 1857. The land making up Seneca Village was later purchased by the city government, and Central Park was built where the village once stood. We have learned from comparing a number of historical documents, such as censuses, maps, and tax records, that more than 220 people lived in Seneca Village by 1857. In our group, we studied one specific family, the Wilson family. The site at which the Wilson family once lived was excavated by archaeologists in 2011, and the soil was found to be filled with objects of value for historians. One of those objects was the fragmented base of a green glass bottle.

Manufacturing Process

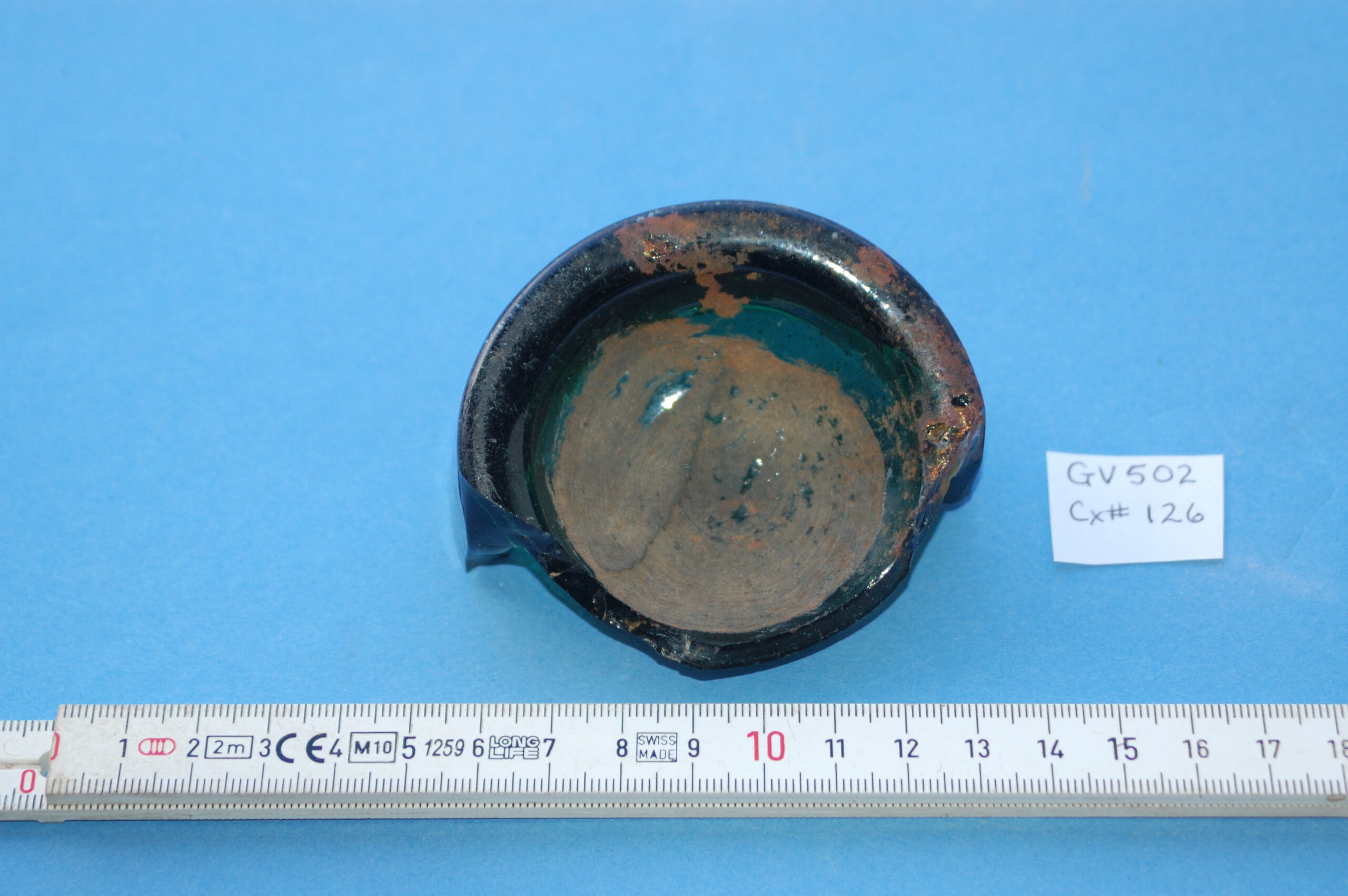

To learn more about the Wilson family, historical archaeologists studied the objects uncovered in the buried ruins of the Wilson’s home–on the land they once owned. In an attempt to add to the research done by these archeologists, I looked at this bottle’s manufacturing process, a key element in identifying its origin. One main feature that helped me to determine its date of manufacture was an iron pontil scar. Pontil scars were an alternative to the small holes left during the glassblowing process; in an attempt to prevent these holes, glassblowers created a new technology. Instead of leaving holes, an iron pontil rod left a metal mark or “scar” on the base of the glass object. Iron pontil rods were used almost exclusively between 1820 and 1850, meaning this bottle was probably produced between those dates (Lindsey 2020).

Figure 1: The iron pontil scar on the Wilson’s glass bottle (Photo courtesy of the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History).

Bottle Shape

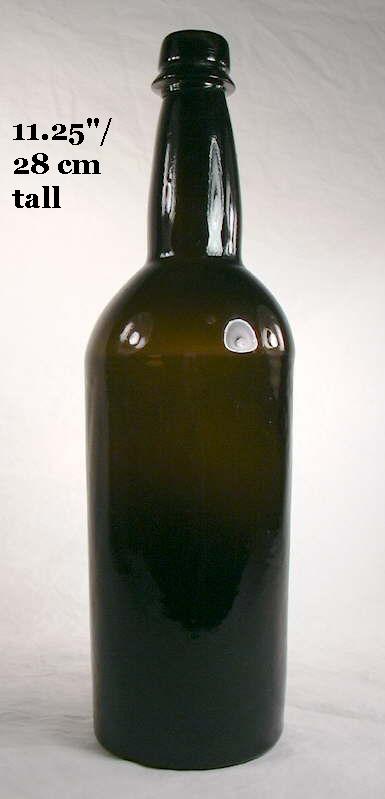

To learn the use and purpose of this bottle, I looked at images of other bottles from the time. Because my bottle was only a fragment, the only elements I was able to compare were the shape and size of the base and the color of the bottle. The bottles most similar in shape, color, and size were all used for either liquor or wine.

Figure 2: A liquor bottle with a base that is similar in shape to my fragment. (Photo courtesy of sha.org, https://sha.org/bottle/Typing/liquor/dipmoldcylinder.jpg:)

Bottle Recycling

In trying to discover the origin of this glass bottle, I ran into a problem–recycling. It cost money to produce and ship glass bottles, so reusing bottles was a popular practice in the 1800s, and a bottle originally filled with one product could later be filled with a completely unrelated one. Many manufacturers also put in place a bottle return system, which would reward customers for bringing back their used bottles (Busch 1987, 70). This makes the origin of the object far less relevant. For example, if a bottle was produced in the Netherlands to hold wine, it could have been reused by a Manhattan shop owner to hold mineral water (Lindsey 2020). But, typically, bottles bought back by stores would be re-used for their original purpose. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that even if the Wilsons were using the bottle for something else, they originally purchased it containing the liquid consumers typically associated with the shape and color of the bottle, which most likely would have been wine or liquor.

Context and Relationship to Seneca Village

Drinking Culture in the 1800s

With the assumption that this bottle was used for wine or spirits, I wanted to learn about what this meant for the Wilson family. To do this, I needed to explore the culture around alcohol in the time period the Wilsons lived in Seneca Village. The most important cultural movement related to drinking in that time period was the Temperance Movement. This reform practice was born out of Native American communities, where the introduction of alcohol by early colonists had destroyed communities (Mancall 1997, xi-xii). Although the Temperance Movement was originally controlled by Native Americans trying to stop drinking in their own communities, it was taken up as a nationwide effort, conducted primarily by the church to reduce drinking and stop people from drinking hard liquor.

A second important piece of context is that enslaved people were generally forbidden from drinking, as slave owners spread the belief their slaves could not handle being intoxicated as well as their white masters (Chrzan 2013, 67).

How does this relate to Seneca Village, the Wilsons, and Kitchen and Table?

An important consideration when discussing drinking in Seneca Village is that very few bottles were excavated in the Wilson house. Only three clearly separate wine bottles were excavated, as well as two “unidentified” bottles.

It is difficult to say how the Temperance Movement affected the Wilsons’ lives, but one could guess that it affected the rest of New York’s perception of Seneca Village. Drinking could have provided a reaffirmation of the Wilson’s independence as free Blacks, as enslaved people were not allowed to drink. This reaffirmation could have been a public announcement of their freedom, or it could have been a private, internal way to assert agency. In our modern lives, we still (sometimes) drink to assert our independence.

This agency theory aligns well with the rest of my group’s research. The Wilsons had a clear concept of style–they wanted their dining experience to include visually appealing plates and jugs–which leads us to believe that they were wealthier than New York was led to believe during the construction of Central Park. It is even possible that drinking contributed to the moral image of Seneca Village. This community was depicted by the media at the time as lacking good values and judgement, and, although that was far from true, alcohol could have contributed to that false image. Choosing purchases based on their desires instead of on price shows that the Wilsons had agency over their lifestyles.

Another important factor to consider was the Wilsons’ choice of drink. In the nineteenth century, different drinks were associated with different ethnic groups and classes. For example, rum was thought to be the drink of the poor, while wine was considered to be a drink of the higher classes. Judging by the quantity of bottles found by archeologists, it would appear that the Wilsons chose to put wine on the table on rare occasions, but not rum or whiskey. This indicates not only that they had agency, but that they also had tastes aligned with their economic class.

Works Cited

Busch, Jane. 1987. “Second Time Around: A Look at Bottle Reuse.” Historical Archaeology 21, no. 1: 67–80.

Chrzan, Janet. 2013. Alcohol : Social Drinking in Cultural Context. New York: Taylor and Francis Group.

Engs, Ruth Clifford. 2000. Clean Living Movements: American Cycles of Health Reform. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers.

“Historic Glass Bottle Identification & Information Website.” n.d. Society for Historical Archaeology. https://sha.org/bottle/index.htm.

Mancall, Peter C. 1997. Deadly Medicine: Indians and Alcohol in Early America. United Kingdom: Cornell University Press.