Bowl

The Wilson family is one of the most prominent examples for understanding Seneca Village and its culture. Certain objects, such as a ceramic whiteware bowl, can tell us about their everyday eating style and what their kitchen was possibly like.

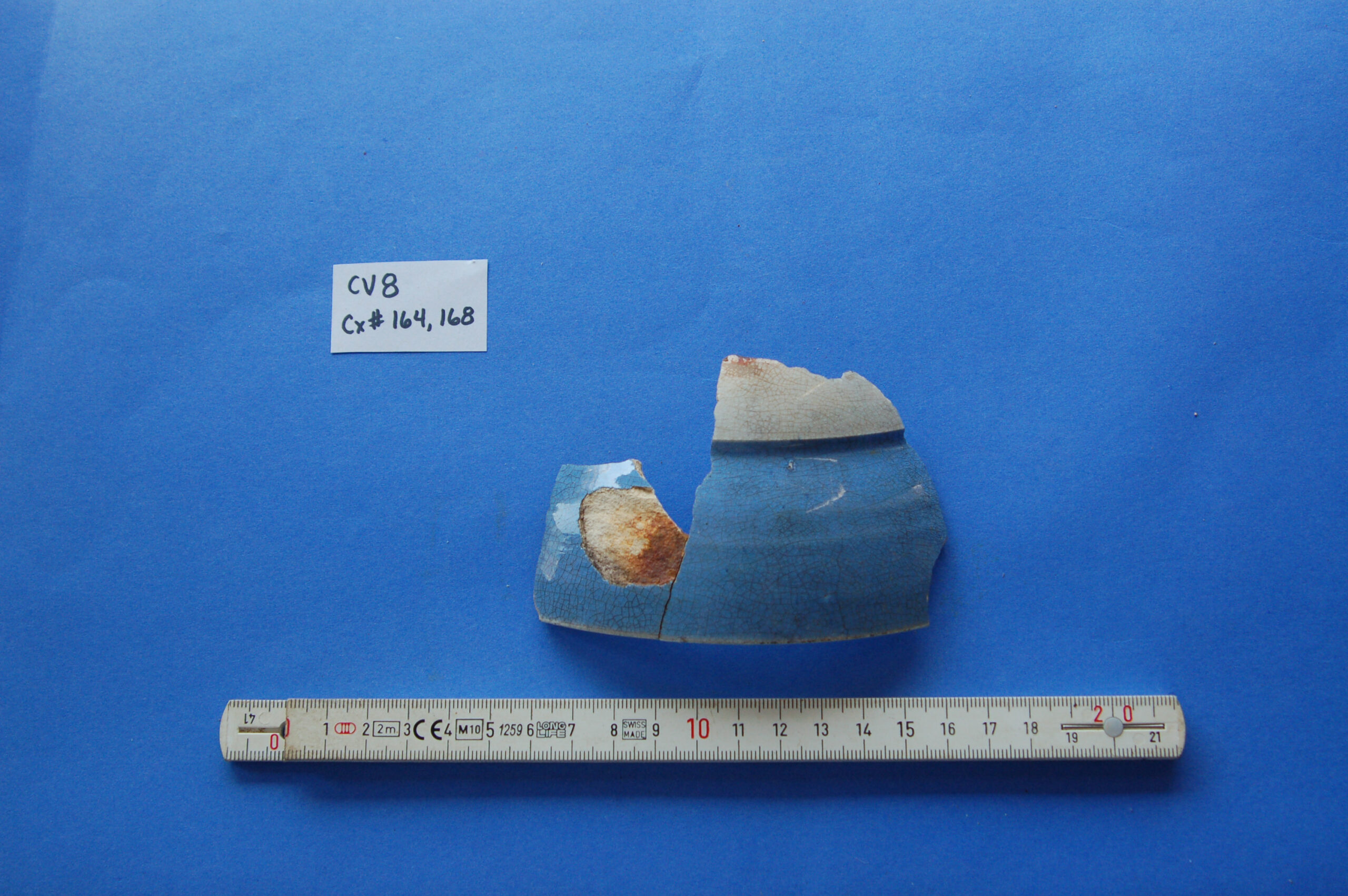

Figure 1: Whiteware bowl, (Photo courtesy of the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History).

History of Bowls

Throughout history, bowls have been a crucial element in dining–the earliest dating back to more than 18,000 years ago. They are a multi-purpose kitchen object, and our lives would be very different without them. In the late 4th millennium BCE, Mesopotamians used bevel-rimmed bowls that were cheaply made and porous, but durable. As time progressed, the design for bowls varied in shape, size, material, and pattern. Specifically, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, numerous English potters, trained by notable English earthenware firms of the time, relocated to America, carrying with them specialized training and information about ceramics (Chipstone 2003). While Americans were successful in producing most ceramics, such as redware and stoneware, they were not as successful in producing and selling other kinds of ceramics. Up until the 1870s, America’s refined whiteware pottery painfully lagged behind pottery from abroad, and most people bought European whiteware (Brooklyn’s Faience Manufacturing Company,” 203)

Figure 2: Bevel Rimmed Bowl, (Photo courtesy of World History Sources).

Background of Bowl

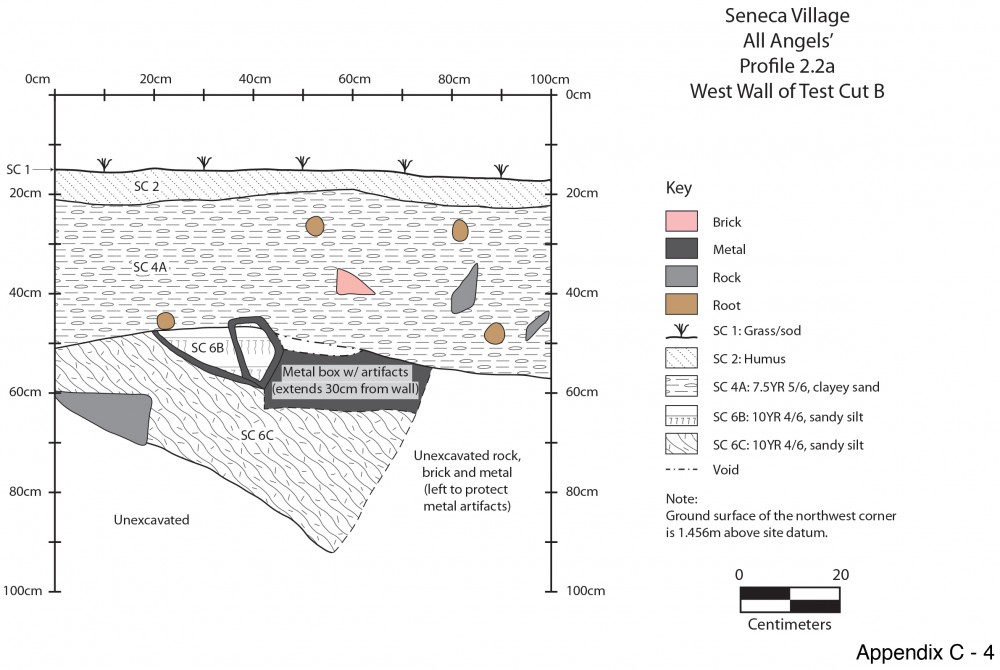

My object is a piece of a blue, slip-banded, dipped whiteware bowl (Figure 1). It was likely made in England between 1815 and 1857 (NYC Archaeological Repository 2020). Archaeologists use a variety of methods in order to date certain artifacts. With artifacts in Seneca Village, archaeologists used relative dating. When doing relative dating, they use clues such as the shape and size of artifacts, where it was discovered, what technology and materials were used to make it, and how it compares to similar artifacts found in the area. By analyzing the site’s stratigraphy (layers of soil built up over time as a result of human or natural activity) and comparing the object to others found at the site, archaeologists were able to successfully identify the layers that corresponded to the documented destruction of the Wilson house in 1857. They found this bowl in that layer, indicating it was left behind by the Wilsons. Therefore, it seems likely that the Wilson family acquired this ceramic from an American importer of European goods, since it was common in the 1850s for Americans to buy European whiteware. Other objects in the Wilson family assemblage can also be dated to the 1850s.

Figure 3: “SC 6C is interpreted as Wilson-family-related domestic material found below the metal sheeting; these objects were presumably left behind by the Wilsons inside their house.” (Image courtesy of The Nan A Rothschild Research Center).

In Relation to Seneca Village and the Wilson Family

The shape of this bowl is somewhat different from most bowls today; it has a double curve (Figure 5), which I have identified as a shape that potters of the period referred to as the Canova Shape (Miller 2011, 12). According to ceramic specialist George Miller, this shape was very common in whiteware bowls and teacups in the nineteenth century.

There are many possibilities for what purpose the Wilson family used this bowl. It could have been used to contain liquids or food that could not be put on a plate. More small bowls like this one were found in the Wilson family assemblage than those of other families. This could imply that their cuisine was different compared to that of their neighbors at the time in New York City, and “traditional African cuisines involve people eating from small bowls which had some starch with rice or cassava and enhanced with protein or vegetables” (Warsh 2019). The Wilson Family, unlike their middle-class white counterparts, did not use matching dish sets with the same prints. This would suggest that no family member could have the same bowl/plate. A possible explanation for this would be that during the era of slavery Black people created their own sense of individualism. The bowl, in relation to the other items in the kitchen and table assemblage, symbolizes the significance of kitchenware in the everyday lives of the Wilson family and their new expression of self, free from slavery.

Figure 4: Inside of bowl. (Photo courtesy of the NYC Archaeological Repository).

Works Cited

“Aesthetic Ambitions: Edward Lycett and Brooklyn’s Faience Manufacturing Company.” 16 June, 2013. Brooklyn Museum. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/exhibitions/3261.

Cheng, Jack. 2005. “Bevel-Rimmed Bowls.” World History Sources. George Mason University. http://chnm.gmu.edu/worldhistorysources/d/250/whm.html.

Goodby, Miranda. 2003. “‘Our Home in the West’: Staffordshire Potters and Their Emigration to America in the 1840s.” Chipstone. http://www.chipstone.org/article.php/75/Ceramics-in-America-2003/?s=emigration.

Miller, George L. 2011. “COMMON STAFFORDSHIRE CUP AND BOWL SHAPES.” Diagnostic Artifacts in Maryland. https://apps.jefpat.maryland.gov/diagnostic/Post-Colonial%20Ceramics/Cup%20Shapes/Essay%20on%20Cup%20&%20Bowl%20Shapes.pdf.

New York City Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center. “Seneca Village.” n.d. NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. New York, NY. http://archaeology.cityofnewyork.us/collection/map/seneca-village.

Warsh, Marie. 7 Feb, 2019. “Uncovering the Stories of Seneca Village.” Central Park Conservancy. https://www.centralparknyc.org/blog/uncovering-seneca-village.

Wright, Matthew. 7 Feb, 2020. “Seneca Village Destroyed to Make Way for Central Park.” Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-4293744/Seneca-Village-destroyed-make-way-Central-Park.html.