Girdle buckle

My artifact from Seneca Village is half of the buckle of a girdle. Girdles were narrow ribbon belts worn around the waist on gowns. It was fashionable for women to wear them beginning in the late 1730s. Girdle buckles were often made in two interlocking parts, and most fastened with a simple single or double buckle of metal, though there is not one characteristic shape (White 2005, 46-47). Figures 1, 3, 4, and 5 show examples of girdle buckles with different designs.

Figure 1: Metal artifact uncovered at the Seneca Village site. (Photo courtesy of the NYC Archaeological Repository)

Artifact Information

Size and Material

This girdle buckle is roughly 3 cm in length by 3 cm in width and about 1-2 mm thick. While girdle buckles could have been made from many materials, such as gold, silver, plated and tinned alloys, brass, or cut steel, the way in which this specific buckle has corroded suggests it is most likely made of a ferrous metal (the principle element is iron) with a brass plating. During the nineteenth century, brass was used to make less expensive belt buckles (White 2005, 47). Brass is composed of about 95% copper and 5% zinc and is yellowish in color (as seen in Figure 2). Brass is also ductile and malleable, which makes it easier for blacksmiths to carve designs into it, hammer and roll it, or plate it onto an array of items. Brass was used to produce many common items such as tableware, personal items of adornment, lighting devices, tools, writing implements, locks, etc. (Light 2000, 4 – 6).

Current Condition

Metal objects are often encountered on archaeological sites, but few pieces are found intact because they corrode and disintegrate when covered by moist earth (Light 2000, 1). This artifact is in relatively good condition, but the green color shown in Figure 2 is evidence of corrosion of the remaining brass, while the rust color shown in Figures 1 and 2 is evidence of iron corrosion (Light 2000, 6). Because the girdle buckle was made from two interlocking parts, the other half of the clasp was most likely separated, and perhaps still remains on another section of the buried Seneca Village ground surface. Furthermore, the buckle could have been plain, as we see it today, or it could have been decorated with design motifs, fabric, and/or gems that were lost over time (White 2005, 47).

Figure 2: Backside of the metal artifact uncovered at the Seneca Village site. (Photo courtesy of the NYC Archaeological Repository)

To Whom it Belonged in Seneca Village

This specific artifact was most likely worn by a woman, given its small size and delicate construction; the girdle buckles worn by men would have been much larger. A police belt from the 1870s (Figure 3) and an early 1900s Mills brand cartridge belt (Figure 4) give a sense of what a complete girdle buckle looks like, and show how the buckles worn by men were thicker and larger.

The Seneca Village girdle buckle was uncovered in the yard between the Webster and Philips houses. George W. Webster owned property valued at $2000 and next-door, William Philips rented a property valued at $500, according to the 1855 New York State Census. The girdle probably belonged to one of the three women in those families: Eliza Webster, the wife of George W. Webster; her 18-year-old daughter from her first marriage, Malvina Hall; or Matilda Philips, the 19-year-old wife of William Philips. In the 1855 New York State Census, these are the only women in their respective family records. It can be assumed, therefore, that the girdle was worn by one of these women. The girdle may have also been passed down from mother to daughter. There are always other possibilities, but these seem to be the most likely, given the prominence of girdles in nineteenth-century women’s fashion.

Women’s Fashion

European Influences

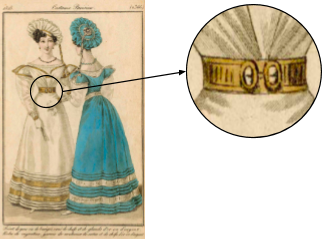

Many nineteenth-century fashion trends originated in Europe, particularly France, and quickly circulated throughout the world through French fashion magazines like Journal des Demoiselles and Modes de Paris. French fashions were copied by American fashion magazines, such as Godey’s Lady’s Book and Peterson’s, and read by women across America (Keckly and Lowe 2015, 124-125). One can assume that women in America replicated these European trends. Figure 5 illustrates what fashionable women in France would have typically worn in the mid-nineteenth century. Although it might be hard to see, both women in the painting are wearing girdles.

Nineteenth-Century Women’s Fashion

In the early 1800s, Neoclassical influences were strong and the high-waisted “empire” silhouette was popular. In the 1820s, the waistline dropped until it was cinched at the natural waist by 1825. Meanwhile, skirts expanded into wide bells, and the “gigot” sleeve (wide at the top and narrow at its bottom) had reached such epic proportions that “the upper arm appeared to be quite double the size of the waist” (Franklin 2020). The most notable change in the fashion of the early nineteenth century was the trend of curvaceous shapes and exaggerated silhouettes–which were provided by the girdle.

Fashion Influences Driven by Literature’s “Ideal Woman”

During this period, women had societal pressures to present themselves in a certain way. Literature and magazines promoted the ideal attributes of “True Womanhood”: piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity (Welter 1966, 152). In order to play her part in society and adhere to her domestic responsibilities, a woman was expected to dress the part as well. Women’s attire and physical appearance acted as an index of womanly virtues such as neatness, simplicity, modesty, and delicacy (Helvenston 1980, 32-33). Without these virtues, she was considered neither the “ideal” woman nor a respectable one.

In the 1800s, decorative girdles cinched a woman’s waist, highlighting the body’s curves and exaggerating its natural shape. This was the ideal standard of beauty and women were quick to follow the style (Romeo, Mathews 2017, 34). Therefore, much of what women wore adhered to the desired look of how a woman “should” dress, and it was not a question of whether or not she liked it.

With this period’s trend of flowing dresses, the body’s shape could be slightly hidden; thus, a girdle was a necessary accessory for a woman to achieve the desired exaggerated silhouette. Underneath their clothes, women laced themselves and their daughters with corsets to ensure they would have “a lady like bearing” (Calvert 1992, 86), and they would also wrap a girdle on the outside of their dresses to reinforce the shape the corset gave them underneath. In this way, girdles could in some respects be seen as a symbolic restriction for women as well, since they were responsible for keeping women within the traditional roles created for them.

Young Girls vs. Women

Beginning from a young age, a girl’s appearance portrayed her place in society. Certain elements of dress could be used to distinguish a girl from a woman or a woman of higher status from one of a lower class. The length and material of clothing changed as a girl became a woman; childhood dresses began as simple muslin frocks and gradually became longer and longer as a girl graduated to the more complex gowns of silk or muslin worn by women (Helvenston 1981, 43; Calvert 1992, 83). It was only once girls joined society that accessories, such as the girdle, were used to show their beauty and mark their womanhood (Calvert 1992, 83). Clothing was very informative; how women presented themselves in society influenced how they were perceived.

Figure 5: Display of Paris Fashion. Print, Plate 19, Costume Parisien (Parisian Costume), Journal des Dames et des Modes (Journal of Ladies and Fashion); Designed by Carle Vernet (French, 1758–1836); engraving, hand-colored with brush and watercolor on off-white paper; 1980-36-2426 (Cooper Hewitt).

Historical Context: Significance of the Girdle for Different Women

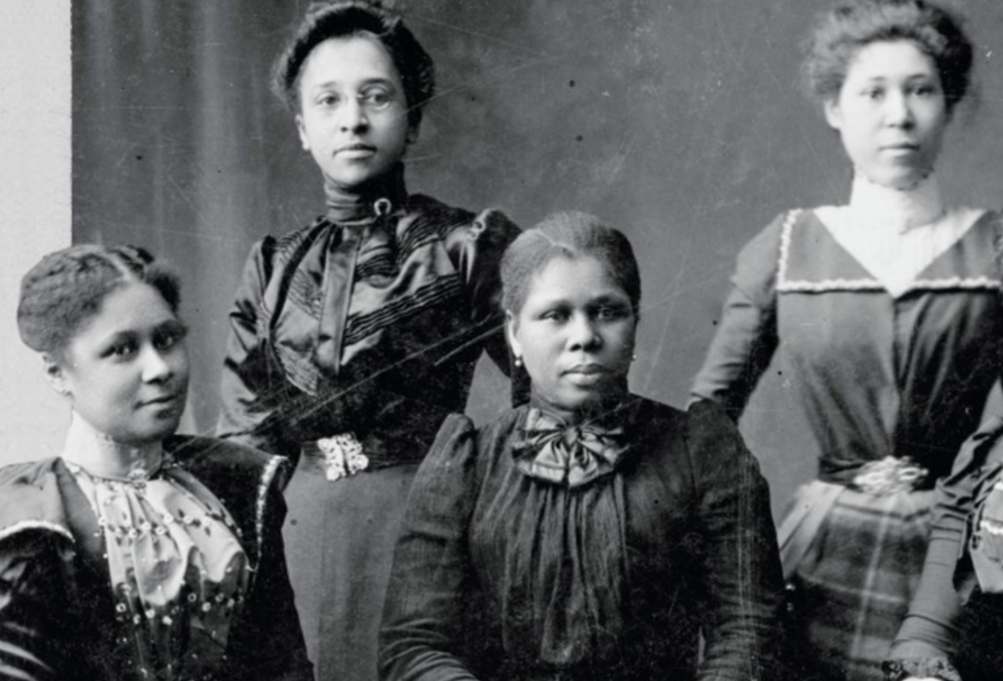

Young girls dressing according to society’s standards marked their acceptance into society, and white women following fashion trends demonstrated their respectability as well as their inclusion in, and understanding of, their social class. For Black women, dress could have been a nonverbal method for them to project their real or desired socioeconomic status, especially to white middle-class audiences (White and Beaudry 2009, 214). Researchers believe it quite common that residents of Seneca Village travelled downtown to the city, whether that be for work or shopping (Meredith Linn, pers. comm.). Already a marginalized group of people in America, there is no doubt those who saw them formulated demeaning stereotypes about them. However, how they presented themselves could counter those assumptions. For instance, through her husband, Eliza Webster owned property, and several other Black women in Seneca Village were also land owners, including Nancy Moore, Angelina Riddles, Diana Harding, and Elizabeth Harding McCollin. In nineteenth-century New York City, it was rare that Black people could own land, let alone Black women, and it was also not very common for white women to own land (Cite Rosenzweig & Blackmar). Thus, I can imagine this was a source of pride, meaning they would be inclined to wear clothing that signaled this achievement and their status in society, especially when surrounded by white people.

The women in Figure 6 show how the way one chooses to present themselves can have an effect on their perceived character, values, and socioeconomic status. Even a small item like a girdle, which most people would dismiss as having no great significance, could have helped construct gender, class, and social identity.

Figure 6: Four women in the 19th century. The belts shown in the photograph offer historic examples of what women wore (image from “The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers” by Hollis Robbins and Henry Louis, Jr Gates)

Connection to Present Fashion

As design historians Laurel Romeo and Delisia Matthews have said, “[b]eauty is merely a reflection of the ideals of society at any given point in history” (2017, 34). Society still presses upon individuals the idea that men and women must wear certain types of clothing, just as it did during the nineteenth century. In western society, the ideal figure for women has transitioned from the small waist and exaggerated silhouette of the early nineteenth century, to a tall, thin silhouette in the present day. This idea is further emphasized by the apparel industry in both the designs and marketing of fashion; oftentimes it is very difficult to find clothing for plus-sized women and this can have mentally damaging effects (Romeo and Mathews 2017, 35). During the nineteenth century, any attempt to change women’s clothing was viewed as an attack on women’s virtue. Conversely, progress can be seen with regards to fashion: more people now are defying society’s standards than before. The lines which dictate what is male and what is female have blurred, and people have the opportunity to wear what they feel inclined to more often.

Although fashions change, the presentation of self and what one chooses to wear remain indications of how individuals want to be perceived by others. Even the smallest accessory can help construct a wearer’s identity. Next time you see someone, do not be so quick to assume a belt is just a belt or a button is just a button. It could mean a lot more.

Works Cited

Calvert, Karin. 1992. Children in the House: The Material Culture of Early Childhood, 1600-1900. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Franklin, Harper. 2020. “1820-1829” Fashion Institute of Technology. https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1820-1829/.

Helvenston, Sally. 1980. “Popular Advice for the Well-Dressed Woman in the 19th Century.” The Journal of the Costume Society of America 6, no. 1: 31-46.

Keckly, Elizabeth, and Ann Lowe. 2015. “Recovering an African American Fashion Legacy That Clothed the American Elite.” Fashion Theory 19, no. 1:115-141.

New York City Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center. 2020. “Seneca Village.” NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York, NY. http://archaeology.cityofnewyork.us/collection/map/seneca-village.

Perry, Claire. 2006. Young America: Childhood in Nineteenth-Century Art and Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Romeo, Laurel D., and Delisia Matthews. 2017. “Society, Fashion, and Being a Plus-size Woman.” International Journal of Design in Society 11, no. 4: 33-43.

Sally Helvenston. 1981. “Advice to American Mothers on the Subject of Children’s Dress: 1800–1920.” Dress, 7, no. 1: 30-46.

Valentine, Genevieve. 2017. “A ‘Portable’ Overview Of A Complex, Compelling History.” National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2017/07/30/537086011/a-portable-overview-of-a-complex-compelling-history.

Welter, Barbara. 1966. “The Cult of True Womanhood: 1820-1860.” American Quarterly 18: 151-174.

White, Carolyn. 2005. American Artifacts of Personal Adornment 1680-1820. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

White, Carolyn L., and Mary C. Beaudry. 2009. “Artifacts and Personal Identity.” In International Handbook of Historical Archaeology, edited by David R. M. Gaimster and Teresita Majewski, 209–225. New York, NY: Springer.