Shoe fragments

Shoes are perhaps one of the most common possessions in the world; they are something that you often wear when you travel anywhere beyond your house—and some even wear them at home.

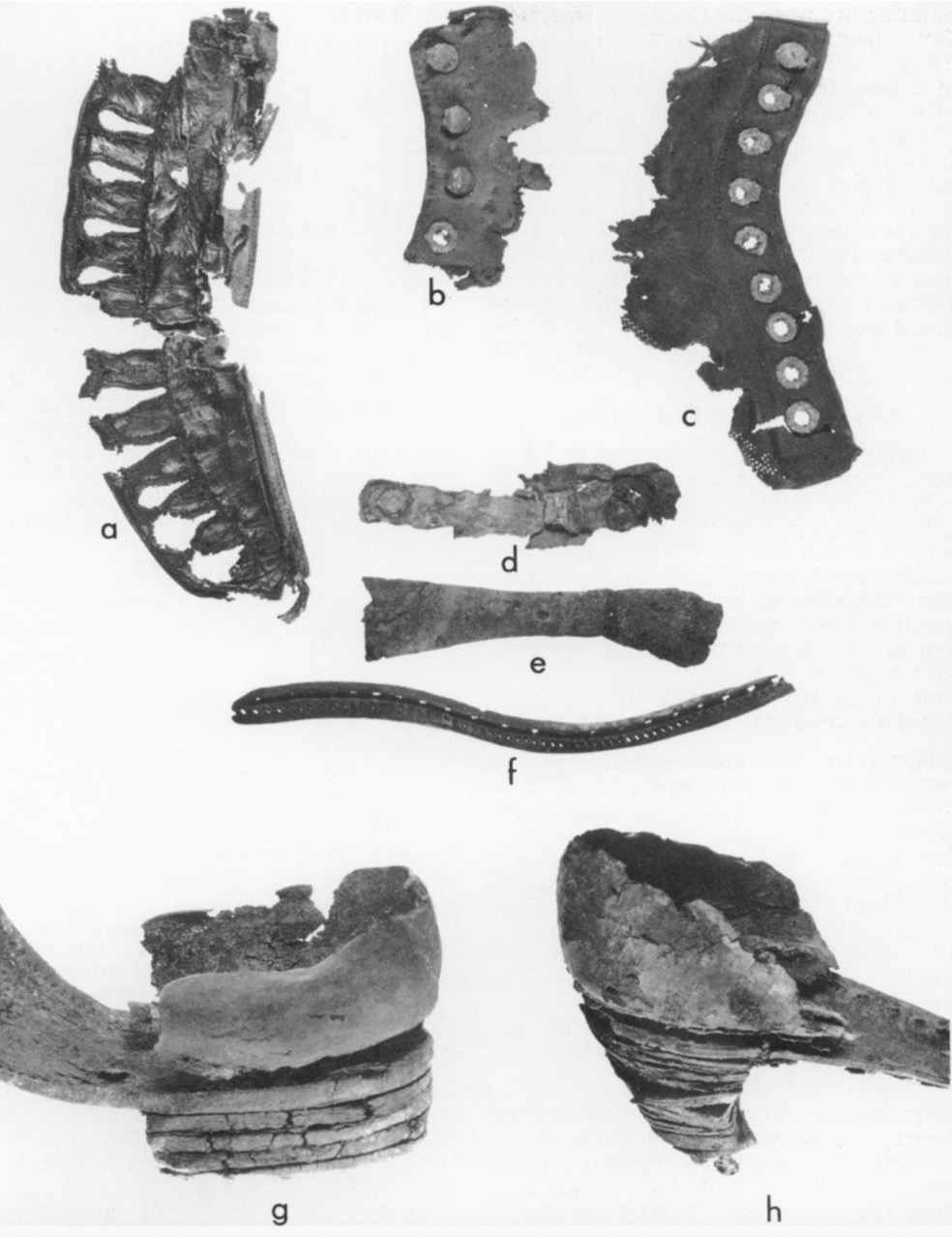

Leather shoes were a common possession of the average American family in the 1850s, particularly among the working class. This was likely true in Seneca Village—a predominantly African-American neighborhood in Manhattan that was destroyed during the construction of Central Park—since most of its residents were working- or middle-class. Several leather shoe fragments were found during an excavation of Seneca Village; three of them can be seen in Figure 1. The leftmost fragment with the tacks is a portion of the sole. It bears resemblance to other shoes found in similar excavation projects, as can be seen in fragment F in Figure 2. The fragments in Figure 1 came from one of the two main excavation areas, a buried ground surface that had been the yard between the houses of the Webster and Philips families.

The inhabitants of Seneca Village sought to elevate their social standing—and the easiest way to do this was dressing well.

Wages and Prices of Shoes

The average wage per day in 1855 was about a dollar (United States Department of Labor 2018, 262). A leather shoe, however, cost approximately $1.47 in Massachusetts—and likely New York—so a shoe would have cost the average working-class person more than their daily wage (Wright 1889, 155).

If the shoe cost over the daily wage of someone in the working class, it suggests that those who were able to afford it were likely in the middle class, if not above it. Someone in the working class, for example, would explore cheaper options for shoes, perhaps shoes made of cloth or another cheap material.

Figure 3: An intact shoe from the 1800s, made of top-grain—high-quality—leather. From Timetoast Timelines, accessed August 4, 2020. https://www.timetoast.com/timelines/1800-1890-shoes

Shoes and Their Social Overtones

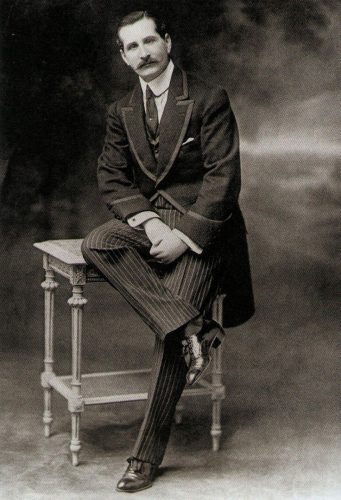

Shoes at the time served the same purpose as shoes serve today: to protect and provide comfort for the feet. But in addition to that, they were also an indication of status. An intact higher-quality shoe from the 1800s can be seen in Figure 3, and a man wearing such a shoe can be seen in Figure 4. Of course, there were still people who went barefoot in New York City which, like today, often signaled poverty.

The types of shoes that one wore indicated one’s social status. Those wearing high-quality shoes, like the ones to which these fragments must have belonged, signaled an elevated status; low-quality shoes, or no shoes at all, signaled a lower status. In the same way, there was a distinction between those who wore fashionable shoes, and those who wore more practical shoes.

Figure 4: A man, likely of elevated status, wearing a shoe similar to the one that was excavated. From Wikimedia Commons. Accessed August 4, 2020. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Main_Page.

Thematic Connections

The leather shoe is thematically consistent with the other objects in this group–the girdle, button, and comb. For instance, many of the objects in this group draw from overseas influences. As is the case today, a lot of fashion was heavily influenced by Europe, in particular France (Bellis 2020). As the title of this group, “Presentation of the Self,” implies, another theme that this object fits into is its role in defining one’s appearance.

More importantly, though, the Websters’ and Philipses’ presentation of themselves–described by these leather shoes, as well using girdles, combs, and buttons–allowed them to appear to the outside world as living a middle-class life–even if they fell squarely in the working class by all other definitions.

Works Cited

Anderson, Adrienne. 1968. “The Archaeology of Mass-Produced Footwear.” Historical Archaeology 2: 56-65.

Bellis, Mary. 18 Aug, 2019. “Everything About The History of Shoes.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/history-of-shoes-1992405.

“The Great New England Shoemakers Strike of 1860.” 22 Feb, 2020. New England Historical Society. https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/great-new-england-shoemakers-strike-of-1860/.

Harris, Leslie M. 2004. In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lubin, Isador, and Frances Perkins, editors. 1966. History of Wages in the United States from Colonial Times to 1928. Revision of Bulletin No. 499 with Supplement, 1840-1928. Detroit: Gale Research Company.

New York City Archaeological Repository: The Nan A. Rothschild Research Center. 2020. “Seneca Village.” NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York, NY. http://archaeology.cityofnewyork.us/collection/map/seneca-village.

Wright, Carroll D. 1889. Comparative Wages, Prices, and Cost of Living [from the Sixteenth Annual Report of the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, for 1885]. Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Company, State Printers.