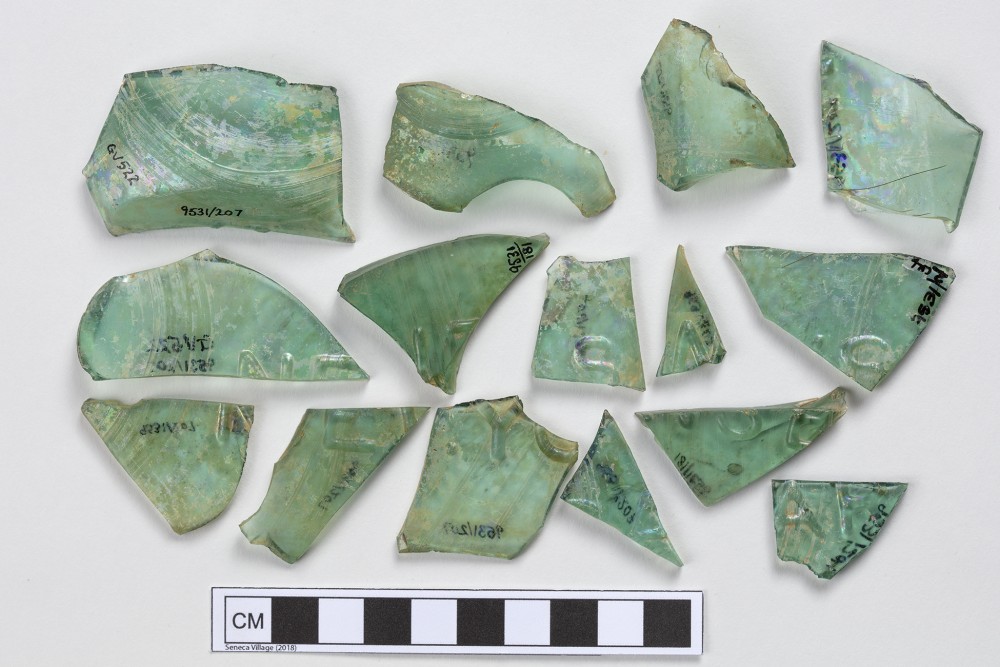

Sarsaparilla bottle

The broken sarsaparilla bottle shown in Figure 1 was excavated from the buried ruins of the Wilson family household. Like many objects recovered as part of the Seneca Village Project, this artifact provides a more nuanced understanding of what the everyday lives of this community might have looked like, as well as how these individuals might have interacted within the greater social fabric of nineteenth-century New York. The sarsaparilla plant, Smilax, is a genus that contains more than 300 species worldwide, with native varieties in China, North America (seen in Figure 2), and regions of South and Central America (Encyclopædia Britannica 2013; eFloras 2020; eFloras 2020; Cafasso 2019). While sold commercially in the form of root beers and other assorted beverages (nineteenth-century brands like Old Townsend’s and contemporary brands such as Sarsi and HeySong Sarsaparilla), the historical use and manufacture of sarsaparilla is rooted in medical practices.

Medical Usage

Introduced in sixteenth-century Europe as “a remedy for venereal complaint,” sarsaparilla was still being used to treat syphilis over three hundred years later in New York City (Shimko 1969, 12). Compared to years past, American medicine in the 1800s had made “considerable progress,” especially in regards to sanitation, and yet the medical field “still remained… a mixture of science, quackery, and tradition” (Dykstra 1955, 401). Working class citizens who could not create home remedies or go to local physicians were especially vulnerable to medical propaganda, “[placing their] trust in the… promises of… marvelous elixirs… which came in bottles and pills” (Dykstra 1955, 401-402). Many of these so-called elixirs provided little, if any, health benefits, despite grandiose and extravagant guarantees. Yet despite the high level of fraud, some of the commercially-sold medicines were actually successful as household remedies (Dykstra 1955, 405-406). Modern research has largely placed sarsaparilla products in the latter category. Recent studies have lent credence to the use of the sarsaparilla plant for cases of dermatitis, arthritis, syphilis, inflammation, liver disease, and cancer (She et al, 2019). Even so, it is undeniable that the abilities of sarsaparilla were overstated in the nineteenth century. For example, Old Dr. J. Townsend’s Sarsaparilla, which was sold as “The Most Extraordinary Medicine in the World,” claimed to purify an individual’s blood, clear pimples, and cure eye sores, ringworm, and dyspepsia (a disease that involved poor digestion and stomach pain)–none of which has been definitively proven since. As with other patent or proprietary medicines of the time, the 18-25 percent alcohol content of this brand was likely its “most ‘effective’ ingredient.” (Wenger 2014). Ultimately, while sarsaparilla remedies from this period likely did provide some relief to consumers, they still would not have been able to fulfill all of their many promises.

Medical Patents and Medicinal Trademarks

The distinction between patent and proprietary (“trademarked”) medicines is critical to understanding both the medical field and bottle collecting in nineteenth-century America. Medical products only obtained patents when they were proven to be “new and useful,” and while these patents protected the intellectual property of the owner, they also “required the disclosure of formulas and contents”–information that would be made available to the public (Fike 1987, 3; Dykstra 1955, 402). As a result, numerous manufacturers opted to sell their articles under a trademark, allowing them to conceal the composition of their medicines and evade government scrutiny, all the while retaining legal protection. Not only did this trend lead to the “era of fraud and misrepresentation” that emerged in 1850, it also fueled the individualization of glass bottles, with different companies tying their name to a variety of colors, sizes, and shapes (Fike 1987, 3). It was during this time, when medical patents were rare (with around 1,500 in the U.S.) and most manufacturers used renewable trademarks, that the sale of sarsaparilla products hit its peak (Fike 1987, 3). Nicknamed the “Sarsaparilla BRA,” the immense popularity of pharmaceutical sarsaparilla products lasted from 1845-1850, although from 1850-1860 these products still had “fair” sales (Shimko 1969, 7-11). It is likely that the Wilson family obtained their sarsaparilla bottle during the BRA, when the use of sarsaparilla for medicinal and collecting purposes was the most widespread.

Collector’s Appeal

With the emphasis on medical trademarks and proprietary medicines in the 1850s, a rich collector’s culture began to emerge in the United States. Sarsaparilla bottles with unusual shapes and colors were more “[highly] priced” than other more standard varieties. Because aqua was considered the most common color, “cobalt, olive green, [and amber]” bottles were the most sought after. “Regular” sarsaparilla bottles were rectangular and had less appeal than ones that were square or round. However, their value could be still increased by combining the ordinary shape with an unusual color, or vice versa (Shimko 1969, 21-22). Additionally, bottles with embossed labels instead of paper were always more expensive, given their rarity at the time, especially among pharmaceutical bottles–“by the 1890s, less than 40 percent of all glass bottles were embossed” (Fike 1987, 4). Finally, the content of the bottle’s label could also improve its standing on the collector’s market. Even the individualized brand that came with different pharmacies and towns was deemed special, as a full collection of bottles came to represent a collection of local histories–“a collection of beauty as great as any art glass collection, and equally as interesting, for what better way to relive the ‘good ole days’” (Shimko 1969, 22). Beyond the bottles themselves, the various advertisements for sarsaparilla bottles had a collector’s culture of their own, with the “different Almanacs…colorful Trade Cards, and… beautiful Calendars” being sought after in equal measure (Shimko 1969, 20). While it is difficult to gauge which groups participated the most in bottle collecting, the marketing and sale of proprietary medicines affected the entire public. It seems like anyone, regardless of their class, could have taken a stab at bottle collecting if they so desired.

The Wilsons’ Sarsaparilla Bottle

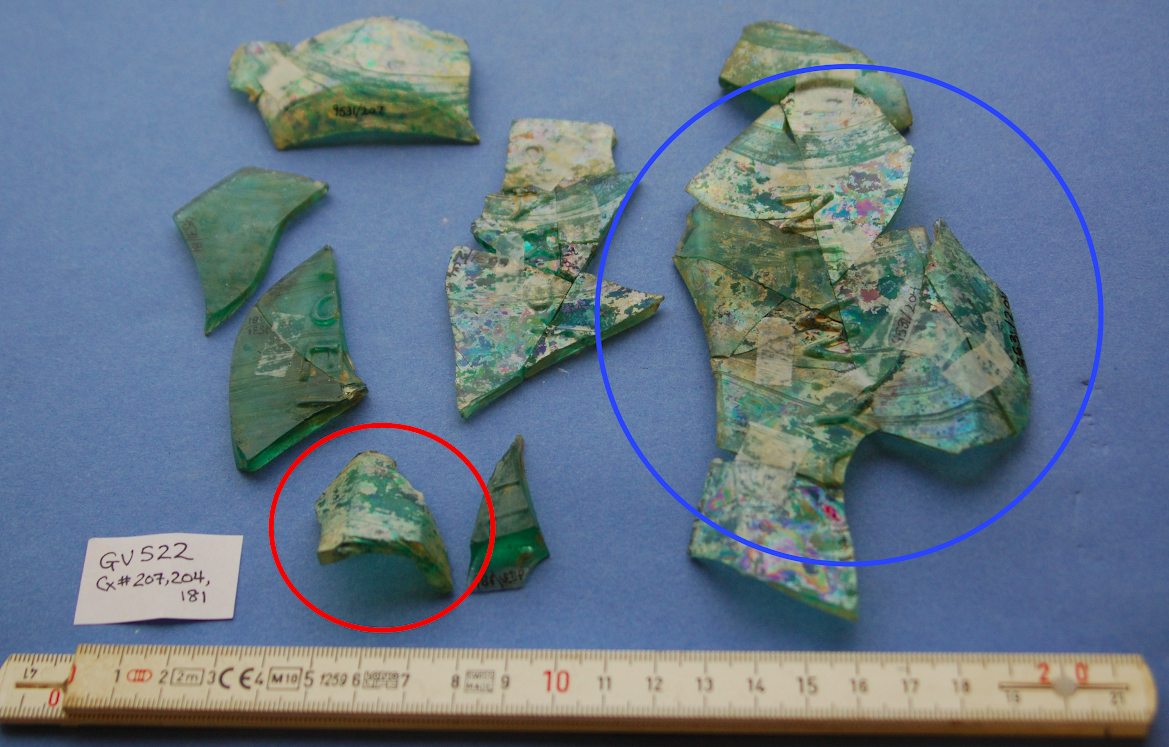

The broken sarsaparilla bottle from Seneca Village was likely a rectangular shape (see Figure 6). The blue circle shows the side of the bottle to have been long and flat with an indent towards the center of the bottle. The red circle shows what seems to be a rounded corner on the bottle. A tall bottle with flat sides and rounded edges would make a rectangular shape; the flat side eliminates a round or circular shape, and the length of the bottle eliminates a square one. Moreover, while the bottle color is not cobalt, amber, or olive green, it does not necessarily reflect the more common aqua color. In direct light (as seen in Figure 1), the glass takes on an almost opaque, sea green color. Aqua colored glass can be slightly blue, as Figure 7 reveals, or a deeper green, as in Figure 8. It is possible this particular sarsaparilla bottle falls somewhere on the aqua spectrum, but it seems more likely that its mixed shade (with a clear combination of blue and green) would have been classified as an “unusual shade of blue,” elevating its collector appeal (Shimko 1969, 21). The bottle’s rectangular shape mixed with a more unusual color, its embossment, and its New York label (shown also by the blue circle in Figure 1) could have raised its economic and cultural value, which might have been an additional motivation for the Wilson family to have procured and saved it.

Connection to Seneca Village

Another incentive for buying medical sarsaparilla could have stemmed from the drink’s alcoholic contents (Wilkie 1996, 119). As shown in Figure 9 (which reveals an embossed SE, as well as what looks like part of a W and N), the bottle was likely a Townsend’s product. Like many other proprietary medicines, Townsend’s had a high alcohol content (with sarsaparilla in particular it was 18-25 percent) and before the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, medical products that contained alcohol could pass as “curative and socially acceptable,” thereby increasing their popularity (Fike 1987, 15). Given that the temperance movement was “rooted in Protestant churches,” it is possible that William Godfrey Wilson and his wife, Charlotte, being members of an Anglican church (All Angels’ Parish), would have been more accepting of alcoholic beverages (Strong, 2018). For the Wilson family, the sarsaparilla bottle may have also acted as a bridge between their African heritage and their participation within nineteenth-century American culture. A key component of African-American ethnomedical beliefs in the 1800s was the emphasis on ‘balancing’ one’s blood; preventing it from becoming “too sweet or bitter… too high or low, too thick or thin, or too dirty” (Wilkie 1996, 120). One of the many health benefits sarsaparilla was said to provide was blood purification. Proprietary medicines whose advertising matched “‘core symbols’ recognized by the community… may have been more desirable to the African-American consumer” (Wilkie 1996, 120). Moreover, the bottles of these commercially-sold medicines were usually reused by the family and could be repurposed to store “traditional’ cures” created by enslaved African-Americans who merged their own culture with Western medical customs upon arrival in the Americas (Wilkie 1996, 120). The sarsaparilla bottle could also have been a reflection of the bottle tree tradition shown in Figure 10, a tradition brought to the Americas as a result of the Atlantic Slave Trade, which dates back to the kingdom of Kongo in the 1770s. While it seems unlikely that the Wilson’s sarsaparilla bottle was used for this purpose (bottle trees were mainly a Southern tradition and the desired color for the glass, which was said to trap evil spirits, was cobalt), the history of bottle trees provides one possible explanation for why the Wilsons, an African-American family, might have felt compelled to buy sarsaparilla (Smithsonian Gardens 2013; Skaggs 2017).

Finally, the use of commercially-produced drugs in the Wilson household might have reflected an increase in independence for its female inhabitants. As these women were considered responsible for providing medical care for the family, many of them were expected to create traditional medicines themselves, a practice which took considerable amounts of time and energy. When proprietary medicines were able to fulfill the “cultural expectations” of African ethnomedical practices for women, it allowed them to “maximize the amount of time they could commit to other domestic and economic pursuits” (Wilkie 1996, 128-129). We know that women in the Wilson family held economic and social agency within Seneca Village. William Godfrey Wilson’s mother, Sarah, owned property and was a prominent member of the community. An African-American household that used commercially-produced drugs, especially ones that confirmed the cultural heritage of the family (i.e., the emphasis on blood treatment), may have created more space for its female members to better their economic and social positions. Ultimately, regardless of whether the Wilsons purchased the sarsaparilla for medical reasons, for the cultural, economic, or personal value of bottle collecting, or for its relatively high alcohol content, the sarsaparilla bottle is yet another reminder of how falsified, racist, and unwarranted the “shantytown” image painted by the media was. The Wilson family’s purchase of the bottle shows that they were engaged with the cultural, political, and economic dimensions of proprietary medicines in nineteenth-century New York. They, like other members of Seneca Village, did not exist in a vacuum–Seneca Village was not an isolated space, but a community that was part of a greater New York and American culture. It is important to remember that the erasure of this neighborhood was not inevitable and that there could have been a present-day New York City where the legacy of families like the Wilsons was better preserved.

Works Cited

“The American Bottle Tree.” 2013. Smithsonian Gardens. https://smithsoniangardens.wordpress.com/2013/02/28/the-american-bottle-tree/.

Cafasso, Jacquelyn. 12 Aug, 2019. “Sarsaparilla: Benefits, Risks, and Side Effects.” Healthline Media. https://www.healthline.com/health/food-nutrition/sarsaparilla.

Dykstra, David. 1955. The Medical Profession and Patent and Proprietary Medicines During the Nineteenth Century. Baltimore:The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fike, Richard. 1987. The Bottle Book: A Comprehensive Guide to Historic, Embossed Medicine Bottles. Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith Books.

“Flora of China.” 2020. eFloras. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=130567.

“Flora of North America.” 2020. eFloras. http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=1&taxon_id=130567.

She, Tiantian, Chuanke Zhao, Junnan Feng, et al. 5 Mar, 2019. “Sarsaparilla (Smilax Glabra Rhizome) Extract Inhibits Migration and Invasion of Cancer Cells by Suppressing TGF-β1 Pathway.” PLoS One. 10(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118287.

Shimko, Phyllis. 1969. Sarsaparilla Bottle Encyclopedia. Oregon: Andrew and Phyllis Shimko.

Skaggs, Holly. 2020. “Build Your Own Bottle Tree Like the Southerners Do and Make Recycled Yard Decor.” Wide Open Country. https://www.wideopencountry.com/bottle-trees-uniquely-southern-tradition/.

“Smilax: Plant Genus.” 20 Mar, 2013. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/plant/Smilax-plant-genus.

Strong, Melissa. 2018. “Women and the Temperance Movement.” Digital Public Library of America. https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/women-and-the-temperance-movement/additional-resources.

Wenger, Lauren. 24 Oct, 2014. “The Cure to All of Your Troubles: Patent Medicines at the Turn of the Century.” The Hershey Story. https://hersheystory.org/the-cure-to-all-of-your-troubles-patent-medicines-at-the-turn-of-the-century/.

Wilkie, Lauren. 1996. “Medicinal Teas and Patent Medicines: African-American Women’s Consumer Choices and Ethnomedical Traditions at a Lousiana Plantation.” Southeastern Archaeology 15, no. 2: 119-131.