Perfume bottle

First Impressions

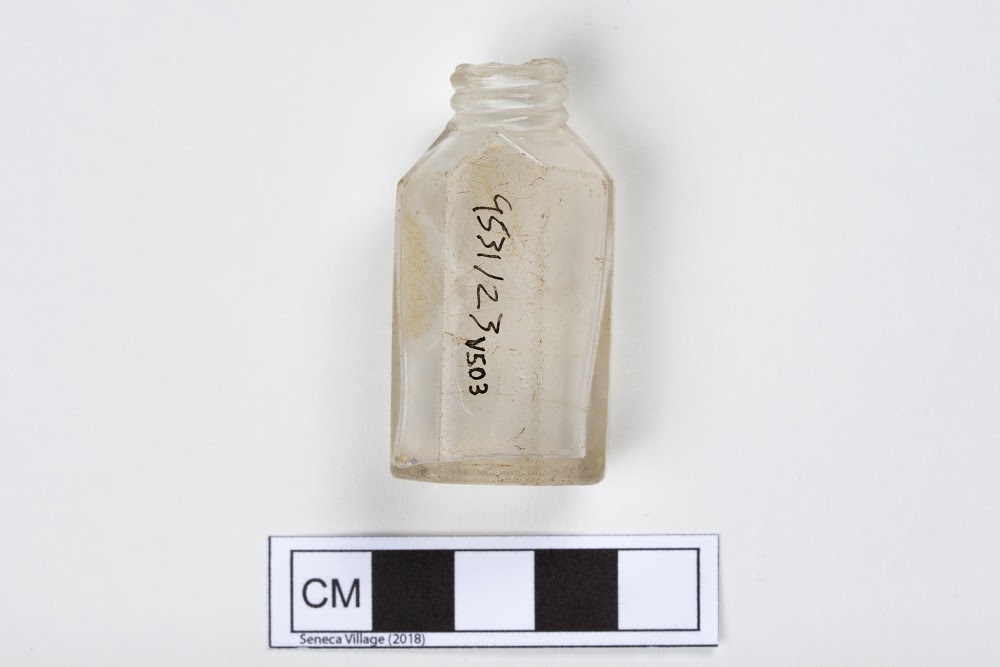

This bottle (Figures 1 and 2) was excavated from the buried ruins of the Wilson family house in Seneca Village. At a glance, it looks very similar to modern perfume bottle designs. It has a threaded lip at the top of the bottle, which can be seen on the tops of most bottles today. This style of bottle top was uncommon before the mid-1850s, when the design was patented (Jones et al. 1989, 81). There is a seam along the sides, indicating that the bottle was made in a two-piece mold (Lindsay 2020, Bottle Bases). This seam does not continue over the base of the bottle. The bottle thus appears to have a post-bottom mold, which refers to a glass mold in which the middle part of the base was made from a separate plate than that of the rest of the bottle (seen in Figures 2 and 3). If this bottle was made using a post-bottom mold, it was most likely produced in either the 1840s or the 1850s, as that was when the practice of a post-bottom molding began (Lindsay 2020, Bottle Bases).

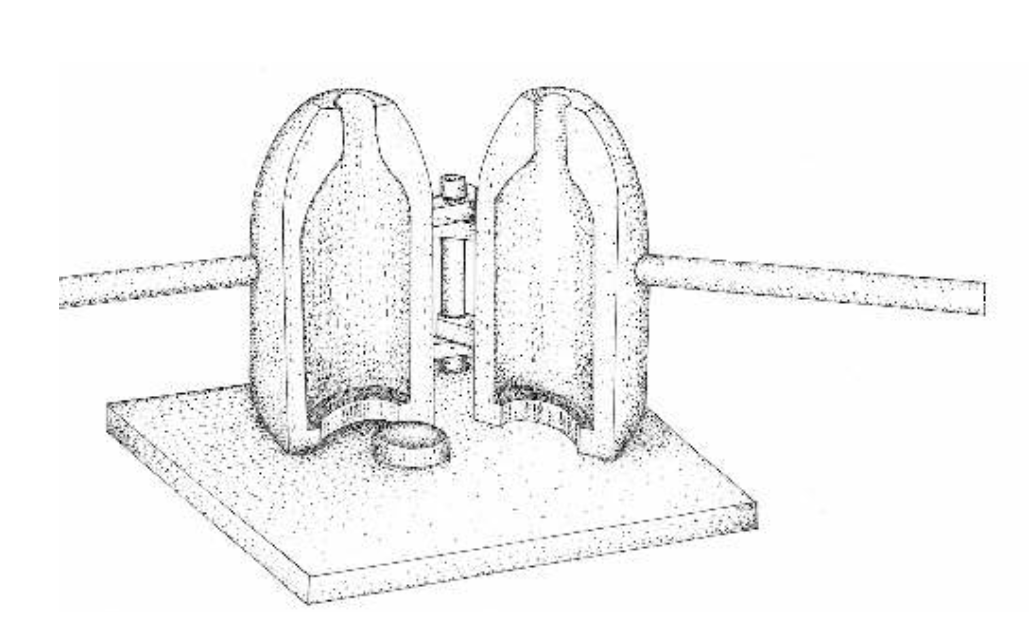

Figure 3: Example of a mold with a post-bottom mod (Lindsay 2020, Bottle Bases)

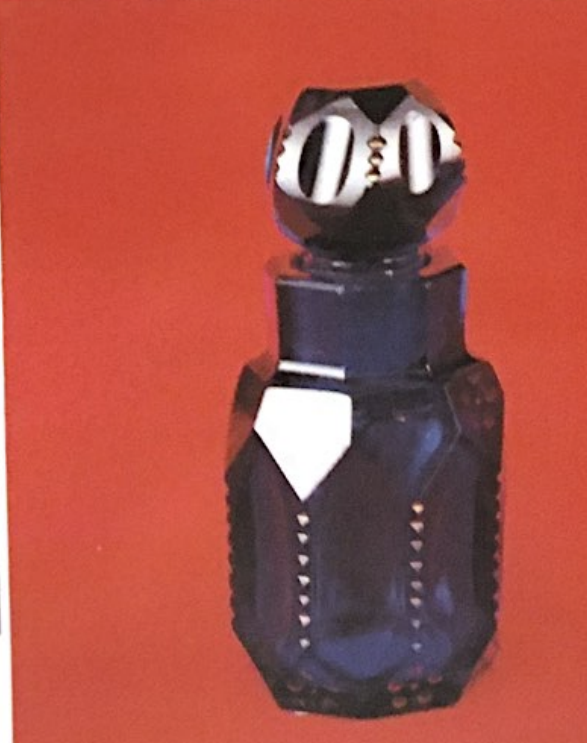

The bottle appears to be made of colorless glass. The brownish discoloration most likely comes from the time this bottle spent underground filled with dirt and from the corroding iron objects nearby. Colorless glass would not have been as common as it is today. Though innovations during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century made the process much easier and reduced the price, colorless glass was uncommon in the early to mid nineteenth century (Lindsay 2020, Bottle/Glass Colors). This was primarily due to colorless glass requiring “silica (sand) almost free of iron and a flux and a stabilizer without noticeable impurities” (Jones-North 1999, 13). Though not as ornate as other bottles from the time (see Figure 4), the colorless glass indicates that this bottle may have been actually more expensive. Figure 4 is made of cobalt-colored glass, a color that was prominently used in perfume bottles during the early nineteenth century (North 1999, 7).

Figure 4: Bristol scent bottle, circa 1820 (North 1999, 13)

The Seneca Village perfume bottle’s threaded lip is interesting, since it was not included on most bottles during this time period. Instead, most perfume/cologne bottles from this time had a flare finish top (Figure 5), which was more common during the early to mid nineteenth century (Lindsay 2020, Bottle Finishes/Closures). A threaded lip is useful for perfume, as it creates a tight seal on the bottle when the cap is on (Lindsay 2020, Bottle Finishes/Closures). This type of cap is useful for a perfume bottle–without it, the liquid could easily evaporate due to its high alcohol content. It is still used today in most perfume bottles. The threaded lip suggests that the bottle was made in a mold, as opposed to being hand-blown, as it was most often made using either a mold or as an applied finish added after the bottle was finished (Lindsay 2020, Tooled Finishes). The presence of the seam running through the threaded lip suggests it was most likely made using a mold.

Figure 5: Example of a flared finish (Lindsay 2020, Mouth-Blown Bottles)

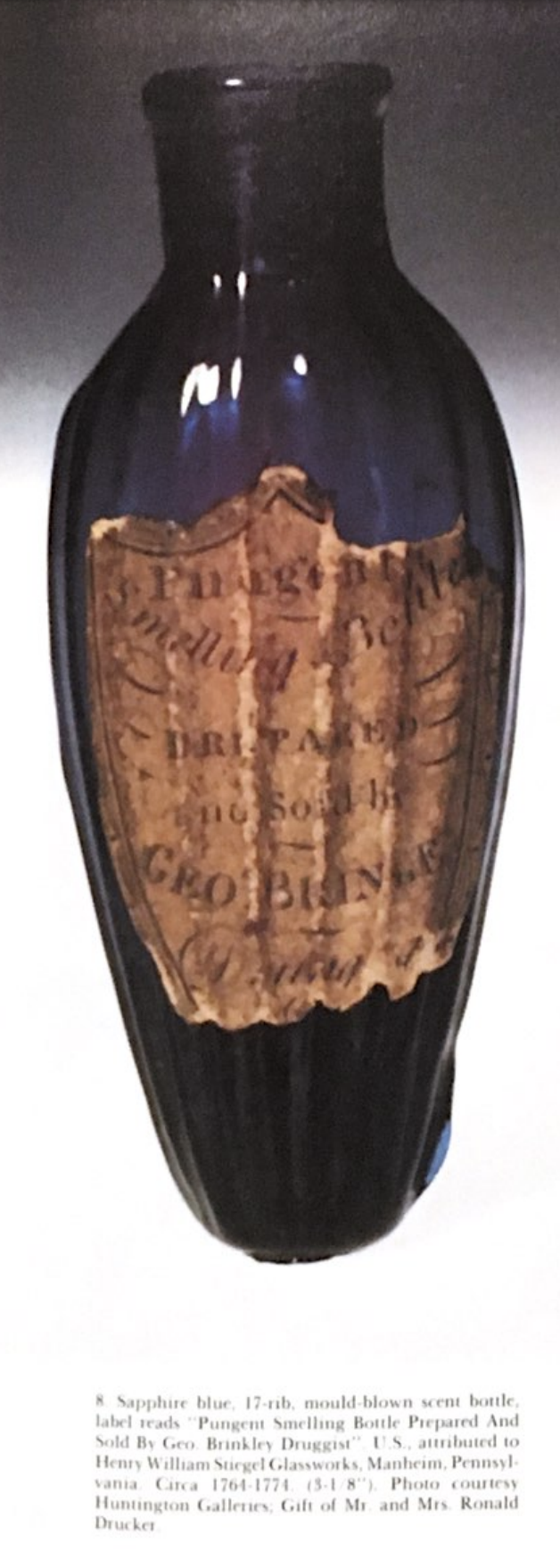

The bottle does not have a visible sign of a manufacturer. There is no maker’s mark or embossing to indicate its maker or the brand of liquid it contained, unlike some companies, such as Pellat, which had branded bottles (North 1999, 11). This means the bottle may have had a paper label. Figure 6 shows how paper labels were used on perfume bottles, although this particular example is from several decades before the Wilson family’s bottle. Without a paper label, embossment, or diagnostic bottle shape, there is no reliable way of telling who specifically made the bottle or the perfume inside it.

Figure 6: Scent bottle with paper label circa 1764-1774 (North 1999, 9)

Historical Context

Perfume bottles in the eighteenth century and before were “luxury item[s]” consumed only by the very rich before the nineteenth century. As raw materials became more widely available, perfume, like many high-end foodstuffs, “diffused partway down the income scale” (Dixon 2018, 263). In the nineteenth century, as prices went down, perfume was available not only for the rich. Despite its comparatively simple design, the rare glass color, as well as the uncommon threaded top, may mean the price of the perfume would have been higher than that of other bottles. The bottle is likely perfume rather than cologne, as the bottle is very small. According to author Jacquelyne Jones-North, “[s]ince more cologne must be used to achieve the same effect as perfume, cologne bottles were usually larger than those manufactured for perfumes” (Jones-North 1999, 11).

Cultural Context

In the nineteenth century, New York smelled horrible. Articles said how the “air [was] heavy with noxious smells” and that “exaltations are constantly ascending from the reeking streets” (Kiechle 2017, 53). The common solution for this smell was either pinched noses or perfume for those who had it (Kiechle 2017, 54). For people living in an urban area in the nineteenth century, perfume was not just for style, but almost as a necessity for going out. In terms of hygiene, perfume would not just be for making someone smell good, but for making their surroundings smell good as well. In 1855 in the Wilson household, where this bottle was found, three members of the house were female. Since the bottle is most likely perfume, as opposed to cologne, it was probably owned by one of them. Two of the three, Mary and Charlotte Wilson, were children (3 and 7 respectively), so the perfume bottle most likely belonged to their mother, the elder Charlotte Wilson. However, considering the ubiquity of perfume, it may have belonged to any of them, or could have been shared. If purchased by the family, then they must have been able to afford the estimated higher cost for this bottle.

On its own, using this to determine the Wilson family’s social class is similar to assuming that because someone has the newest iPhone, they must be rich. However, when considered alongside the other items in this section–such as the toothbrush, another uncommon object to own at the time–the family seems to have lived a comfortable life. In addition to a lifestyle where they could take care of their bodies, the Wilsons owned their property. The people of Seneca Village were seen as squatters living in shantytowns, but the fact the Wilsons had these commodities brings how Seneca Villagers were seen at the time into question. Though even an impoverished family may still have an iPhone, one would not expect a derelict squatter to own one. Yet, the Wilson family, as well as everyone else in Seneca Village, were portrayed as people who would not have access to these objects. But somehow, either through gift, exchange, or purchase, this family owned these objects.

In New York, smell was a reflection of class. Lower class areas smelled worse than upper class ones, a reflection of their poverty (Kiechle 2017, 65). In contrast, middle class families were able to control their smell, due to less crowded homes, access to perfume and cologne, and better living conditions (Kiechle 2017, 66). Despite the people of Seneca Village being portrayed as horrible, squalid people, they probably would have been living better lives than a good amount of the working class people in lower Manhattan. Seneca Village was less crowded, and the existence of a perfume bottle, in addition to other bodily care objects primarily owned by the middle class, shows that this family likely lived a more comfortable life than previously thought. In the present, perfume and cologne are still widely available, especially considering advancements made over the last centuries. However, understanding its use during the nineteenth century can help us understand how the people of Seneca Village lived and might have actually thrived, especially compared to others living in New York at the time.

Works Cited

Dixon, Tara. Oct 2018. “Scents and Soda: French Perfume, American Glassworks, and the Rise of the Retail Water Industry.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 142, no. 3: 239–67.

Jones-North, Jacquelyne Y. 1999. Perfume, Cologne and Scent Bottles, Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing.

Jones, Olive and Catherine Sullivan. 1989. The Parks Canada Glass Glossary (revised edition). Quebec, Canada: National Historic Parks and Sites, Canadian Parks Service, and Environment Canada.

Kiechle, Melanie A. 2017. Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America. Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Lindsay, Bill. 2020. “Part II: Types of Styles of Finishes – Page 2.” Society of Historical Archaeology and Bureau of Land Management. sha.org/bottle/finishstyles2.htm#Flare%20or%20Trumpet.

Lindsay, Bill. 2020. “Bottle/Glass Colors.” Society of Historical Archaeology and Bureau of Land Management. https://sha.org/bottle/colors.htm.

Lindsay, Bill. 2020. “Household Bottles (non-food related).” Society of Historical Archaeology and Bureau of Land Management. sha.org/bottle/household.htm#Perfume/Cologne.

Lindsay, Bill. 2020. “Bottle Finishes (aka “Lips”) & Closures.” Society of Historical Archaeology and Bureau of Land Management. https://sha.org/bottle/finishes.htm#Mouth-blown%20bottles.

Lindsay, Bill. 2020. “Bottle Bases.” Society of Historical Archaeology and Bureau of Land Management. https://sha.org/bottle/bases.htm#Mold-blown%20bottle%20bases.

New York State Census (NYSC). 1855. Census Returns for the Sixth Ward of the City of New York in the County of New York. Manuscript, Department of Records and Information, Municipal Archives of the City of New York, New York, NY.